As humans put more and more heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere, the Earth warms. And the warming is causing changes that might surprise us. Not only is the warming causing long-term trends in heat, sea level rise, ice loss, etc.; it’s also making our weather more variable. It’s making otherwise natural cycles of weather more powerful.

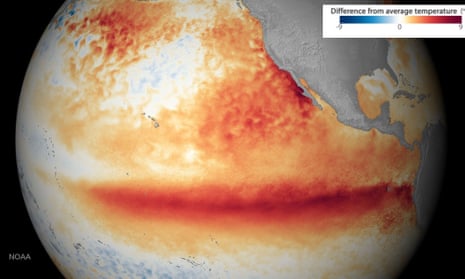

Perhaps the most important natural fluctuation in the Earth’s climate is the El Niño process. El Niño refers to a short-term period of warm ocean surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific, basically stretching from South America towards Australia. When an El Niño happens, that region is warmer than usual. If the counterpart La Niña occurs, the region is colder than usual. Often times, neither an El Niño or La Niña is present and the waters are a normal temperature. This would be called a “neutral” state.

The ocean waters switch back and forth between El Niño and La Niña every few years. Not regularly, like a pendulum, but there is a pattern of oscillation. And regardless of which part of the cycle we are in (El Niño or La Niña), there are consequences for weather around the world. For instance, during an El Niño, we typically see cooler and wetter weather in the southern United States while it is hotter and drier in South America and Australia.

It’s really important to be able to predict El Niño/La Niña cycles in advance. It’s also important to be able to understand how these cycles will change in a warming planet. Fortunately, a study just published in Geophysical Research Letters helps answer that question. The authors include Dr. John Fasullo from the National Center for Atmospheric Research and his colleagues.

El Niño cycles have been known for a long time. Their influence around the world has also been known for almost 100 years. It was in the 1920s that the impact of El Niño on places as far away as the Indian Ocean were identified. Having observed the effects of El Niño for a century, scientists had the perspective to understand something might be changing.

For example, in 2009–2010, intense drought and heat waves gripped the Amazon region – far greater than expected based on the moderate El Niño at the time. In addition, from 2010 to 2011, severe drought and heat waves hit the southern USA, coinciding with a La Niña event. Other extreme weather in the US, Australia, Central and Southern America, and Asia stronger than would be expected from El Niño’s historical behavior have raised concerns that our El Niño weather may be becoming “supercharged.”

To see if something new was happening, the authors of this paper looked at the relationship between regional climate and the El Niño/La Niña status in climate model simulations of the past and future. They found an intensification of El Niño/La Niña impacts in a warmer climate, especially for land regions in North America and Australia. Changes between El Niño/La Niña in other areas, like South America, were less clear. The intensification of weather was more prevalent over land regions.

So, what does this mean? It means if you live in an area that is affected by an El Niño or La Niña, the effect is likely becoming magnified by climate change. For instance, consider California. There, El Niño brings cool temperatures with rains; La Niña brings heat and dry weather. Future El Niños will make flooding more likely while future La Niñas will bring more drought and intensified wildfire seasons.

Unsurprisingly, we’re already seeing these effects, with record wildfires in California fueled by hot and dry weather. We are now emerging from a weak La Niña, so we would expect only a modest increase in heat and dryness in California. But the supercharging of the La Niña connection is likely making things worse. We would have California wildfires without human-caused global warming, but they wouldn’t be this bad.

Dr. Fasullo nicely summarized the findings of the paper:

We can’t say from this study whether more or fewer El Niños will form in the future — or whether the El Niños that do form will be stronger or weaker in terms of ocean temperatures in the Pacific. But we can say that an El Niño of a given magnitude that forms in the future is likely to have more influence over our weather than if the same El Niño formed 50 years ago.

And this conclusion can be extended to many other situations around the planet. Human pollution is making our Earth’s natural weather switch more strongly from one extreme to another. It’s a weather whiplash that will continue to get worse as we add pollution to the atmosphere.

Fortunately, every other country on the planet (with the exception of the US leadership) understands that climate change is an important issue and those countries are taking action. It isn’t too late to change our trajectory toward a better future for all of us. But the time is running out. The Earth is giving us a little nudge by showing us, via today’s intense weather, what tomorrow will be like if we don’t take action quickly.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion